In this blog, I will be referencing data in the public domain to compare and contrast the studies submitted to FDA to support label expansions for two marketed products and the similarities and differences in the FDA review and outcomes. By way of disclosure, PROMETRIKA has not worked on either of the two products discussed and all information presented is in the public domain (the October 5, 2023 Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) FDA slides and ODAC vote for the first and the April 1, 2022 Clinical Review and Evaluation and Statistical Review for the second).

The idea for this blog came after listening to the October 5, 2023 FDA Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee (ODAC) meeting where the results of the CodeBreaK 200 study of KRAS inhibitor sotorasib (Drug A) in NSCLC were discussed. This study was submitted to FDA to support label expansion and confirmation of clinical benefit to convert the previously granted accelerated approval (AA) to full approval. The primary endpoint in the study was Progression Free Survival (PFS). Some of the discussions reminded me of information I had reviewed regarding the label expansion study of a biologic product, axicabtagene ciloleucel (Biologic B), a cell-based therapy for the treatment of large B-cell lymphoma. While the two agents and their indications are very different, both studies used time to event endpoints (PFS for the Drug A and Event Free Survival (EFS) for the Biologic B). As the focus of this blog is not the products themselves, but the FDA review of the studies submitted and the lessons learned, for the remainder of the discussion, I will refer to them as Drug A and Biologic B.

Drug A - A targeted small molecule for the treatment of KRAS Mutated NSCLC

After their initial review of the data from this study, the FDA turned to ODAC for an opinion on whether the PFS treatment effect could be reliably interpreted with the data presented. It should be pointed out that a second study was ongoing which could also be used to support conversion of AA to full approval if the study under review was not sufficiently robust. As a result, the potential that this drug could be removed from the market if FDA did not approve this supplement was not an issue. At the October 5, 2023 meeting, ODAC agreed with the FDA. In December 2023, the Sponsor reported that they had received a Complete Response Letter and a new postmarketing requirement (PMR) for an additional confirmatory study to support full approval. (Reference: Amgen 26Dec2023 press release).

Let’s take a few minutes to review the design of the study that the FDA and ODAC reviewed in 2023.

This was an open label study in which patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC with a KRAS G12C mutation, who had received one or more prior therapies, were randomized 1:1 to Drug A or docetaxel (the standard of care or SOC). The primary endpoint was progression-free survival (PFS) by blinded independent central review (BICR), with secondary endpoints of overall survival (OS), overall response rate (ORR), and duration of response (DOR). In this study, patients who progressed on the SOC, by investigator assessment with confirmation of progression but before the BICR was completed, were allowed to crossover to Drug A.

The results of the efficacy analyses are presented below:

|

|

|

Drug A |

SOC |

Hazard Ratio |

|

Primary Endpoint |

PFS per BICR1 |

5.6 months |

4.5 months |

0.66 |

|

Secondary Endpoints |

OS1 |

10.6 months |

11.3 months |

1.01 |

|

ORR1 |

28% |

13% |

|

1 Reference: Page 34 of the FDA presentation at the October 5, 2023 ODAC Meeting

The study appears to have met its primary endpoint of PFS per BICR. Thus, one might ask the question, what was the issue here?

As always seems to be the case, the devil is in the details.

While there was a statistically significant difference in PFS between the two treatment groups, this difference was not as large as one might have liked (1.1 months or 5 weeks), which raised the FDA question of whether this was a robust and clinically significant result. In addition, there was no survival difference between the 2 treatment arms. While FDA did not require a statistically significant survival advantage in favor of Drug A in a study where survival is not the primary endpoint, they would have liked to have seen a trend favoring it (Reference: Pages 40 and 60 of the FDA presentation at the October 5, 2023 ODAC Meeting).

Digging further into the data, as FDA always does during the review of an application, the FDA found additional items in the conduct of the study. This gave the FDA cause for concern, and these items were raised in the ODAC presentation. As we will point out later, many of these items are not completely unexpected and certainly do not imply that the Sponsor was lax in study conduct. Let’s take a minute and review these. (Reference: Pages 47-59 of the FDA presentation at the October 5, 2023 ODAC Meeting)

- There were more early dropouts in the SOC arm than in the Drug A arm (13% vs 1%). These patients were censored on Day 1, which could lead to an over-estimation of the PFS treatment effect of Drug A if these patients (mostly on the SOC arm) would have had better outcomes if they had been treated in the study.

- Crossover of patients from the SOC arm to the Drug A arm after disease progression was allowed after Investigator assessment of confirmed progression (26%) but before BICR. The Investigator was not blinded; thus, may have more diligently scrutinized patients in the SOC arm for progressive disease (PD).

- Discrepancies between confirmed Investigator assessments of progression and the subsequent BICR, which triggered sponsor requested BICR re-reads. From FDA’s perspective, these discrepancies may have favored the Drug A arm.

When FDA conducted additional analyses on the PFS endpoint, the conclusion was that the PFS benefit (5 weeks) was less than the imaging interval (6 weeks); and, although the hazard ratio (HR) remained relatively consistent, FDA concluded that in the worst-case scenario, the median PFS difference could be as small as 5 days. (Reference pages 38-39 of the FDA presentation at the October 5, 2023 ODAC Meeting).

Additional FDA analyses of the OS endpoint yielded no change in OS results after adjusting for crossover. FDA concluded that the crossover was unlikely the reason for the observed lack of favorable OS difference between the treatment and SOC arms (Reference pages 40 and 60 of the FDA presentation at the October 5, 2023 ODAC Meeting).

FDA concluded that due to small PFS benefit, positive and expected differences in ORR, no OS trend, and issues with study conduct, the study was not sufficiently robust to support conversion of accelerated approval to full approval. (Reference page 63 of the FDA presentation at the October 5, 2023 ODAC Meeting).

Biologic B - Biologic for the Treatment of Relapsed or Refractory B‑cell Lymphoma

Let’s now look at the FDA assessment of another product that was studied in a trial with a time-to-event primary endpoint of EFS. In this study, to add an indication to the previous approval, Biologic B was compared to salvage therapy followed by transplant, which was the SOC for patients with this indication at the time the study was conducted. The primary endpoint was EFS as determined by BICR. Secondary endpoints were OS, PFS by BICR, and ORR (https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/yescarta-axicabtagene-ciloleucel). The results of the study as discussed in the April 1, 2022 Clinical Review and Evaluation and Statistical Review are summarized below:

|

|

|

Biologic B |

SOC |

Statistical Significance |

|

Primary Endpoint |

EFS per BICR1 |

8.3 months |

2 months |

HR 0.4 (p<0.0001) |

|

Secondary Endpoints |

OS2 |

Not reached |

25.7 months |

HR 0.708 Difference not statistically significant |

|

ORR3 |

83% |

50% |

Statistically significant difference |

|

|

PFS by BICR4 |

14.9 months |

5 months |

HR 0.56 |

HR = Hazard Ratio

1 Reference: Table 6 of April 1, 2022 Statistical Review

2 Reference: Table 8 of April 1, 2022 Statistical Review

3 Reference: Table 7 of April 1, 2022 Statistical Review

4 Reference: Table 9 of April 1, 2022 Statistical Review

You may be asking whether FDA found issues with this filing and how were they viewed. While the answer to the first question is yes, what is interesting are the analyses, results and conclusions. The potential issues were:

- The SOC arm had a higher rate of new lymphoma therapy than the Biologic B arm, (35% vs. 5%). This is important as new therapy was considered an EFS event; i.e., failure of the study therapy. For an open-label trial, the decision by Investigators to start a new therapy may potentially subject the study to bias as Investigators may tend to administer new lymphoma therapy more readily in the SOC than the Biologic B arm.

How was this concern mitigated?

A conservative sensitivity analysis was conducted. The EFS was recalculated with the exclusion of some of the control group patients and the result still favored the Biologic B arm; thus, the sensitivity analysis demonstrated the robustness of the EFS results. - There was a higher proportion of disease progression (46% vs. 42%) and higher proportion of death (6% vs. 3%) in the Biologic B arm compared with the SOC arm.

How was this concern mitigated?

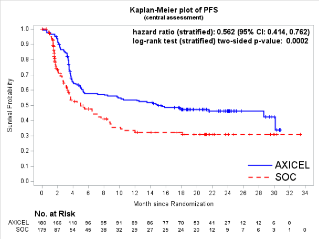

Here again the devil is in the details. While this was the case, in reviewing the Kaplan-Meier (KM) curve of PFS by BICR (see below), the Biologic B arm was consistently above that for the SOC arm, indicating that Biologic B was superior in that it delayed PFS events compared with SOC. Also, censoring for the Biologic B arm tended to appear in the tail part of the KM curve due to ongoing response, whereas censoring happened more frequently at the beginning of the KM curve for the SOC arm due to administration of new lymphoma therapy.

Reference: Figure 11 of April 1, 2022 Clinical Review and Evaluation - Interpretation of the OS results was complicated by the crossover events: 56% of participants in the SOC arm who progressed by BICR crossed over to the Biologic B arm.

How was this concern mitigated?

In this study, it is important to remember that BICR-assessed progression was used for the crossover determination. As a result, there was not an issue with concordance between Investigator-assessed progression and progression by BIRC.

While the difference in OS between the two arms was not statistically significant, the direction of the observed treatment effect was in favor of Biologic B and was consistent with the EFS and PFS data. There was no detriment to OS with the second line use of Biologic B compared to SOC, despite the fact that the results may have been confounded by the crossover.

FDA concluded that, though the EFS endpoint in an open-label trial has its limitation, the efficacy of Biologic B was not solely evaluated on this endpoint. Efficacy was also evaluated on the secondary endpoints ORR, PFS, and OS. Also, for the PFS endpoint, new lymphoma therapy was not an “event” as for EFS but instead triggered censoring. In addition, the OS endpoint did not distinguish new lymphoma therapy from protocol-specified therapy. The impact of potential bias of new lymphoma therapy administration was minimized in the assessment of these two endpoints. The primary endpoint of EFS was statistically and clinically significantly greater in the Biologic B arm, and the difference between the two arms was maintained when using conservative sensitivity analyses. In addition, ORR and PFS were clinically and statistically significantly different in favor of Biologic B, providing additional efficacy support. While the OS did not cross the boundary for statistical significance, the data were numerically in favor of Biologic B.

Conclusions

So, you may ask – why did one study not make the grade and the other did? The endpoints were similar; however, in the Biologic B study, the primary endpoint (EFS) withstood the conservative sensitivity analyses that FDA conducted. The secondary endpoints (OS, ORR PFS) all favored Biologic B and thus supported the primary result. For Drug A, while the primary endpoint (PFS) treatment comparison was statistically significant, the magnitude of the benefit was not clinically significant and was not great enough to withstand the sensitivity analyses. Also, a trend in OS was not seen; the results numerically favored the SOC arm. In total, the results of the Drug A study were just not robust enough.

While study design is important, one cannot overlook the characteristics of the patient population and study conduct issues. We also have to remind ourselves of the basic objective of cancer therapy: to help patients live longer and/or live better. When we consider this, we are reminded of the importance of the survival data regardless of whether it is a primary endpoint or if the study is powered to see a statistically significant difference. At a minimum, a favorable trend is very important. When one sees numerical differences (regardless of statistical significance) that do not favor the treatment being tested, we may have to conclude that the benefits of treatment do not outweigh the risks, and we may not be able to rule out the possibility that survival is being compromised.

So, what are the lessons learned here? From my perspective, one is the importance of survival data as outlined above. The second is the nuances of study conduct. Each decision we make regarding study conduct may have implications . While crossover studies are not preferred by FDA, they are routinely conducted but the details of how the crossover is done (e.g., based on investigator or BICR assessment) may have consequences. This is also the case for other study design and/or execution issues.